Agua- The importance of water in the fermentation of Mezcal

In my last blog post, I touched on the natural and wild fermentation of our agave, using natural microbes in the air as wild yeast. I want to elaborate a little more on the fermentation process and specifically, the water used in fermentation. While the agave mash is fermenting, the water simmers the agave for days, playing a critical role in defining the final quality and flavour profile of Bandida Mezcal.

So, what exactly is a microbe? It's a microscopic, single-celled organism. These tiny life forms perform anaerobic respiration, breathing without oxygen, and in the process; they exhale CO2.

You can easily speed up the process of fermentation by using diffusers or increasing the water temperature, or even boiling it. However, the secret to crafting high-quality Mezcal lies in using lower temperatures around 18-25 degrees, and allowing a longer fermentation period. Diffusers are employed by some producers to extract sugars from the agave with over 95% efficiency. Unlike the traditional or artisanal method that uses mechanical pressure, these producers employ hot water and mechanical devices to accelerate fermentation.

Fermentation often seems complex, but it's really quite straightforward. Wild microbes consume the sugars in the agave mash and, through anaerobic respiration, they produce alcohol and CO2 as byproducts.

We leave the agave mash in Oak wooden barrels, and the bubbles you see are the CO2 molecules escaping from the fermenting liquid.

For those interested in the physics / maths, the equation for fermentation is:

C6H12O6 (sugar) → 2C2H5OH (ethanol) + 2CO2

During this process, the microbes exhale ethanol and CO2, with ethanol leaving through their cell membranes and CO2 being released as a gas.

The local climate, particularly temperature and humidity, impacts the microbes, influencing the unique flavours of our Mezcal. These microbes also produce secondary metabolites that enhance the aroma, taste, and complexity of the final product.

The production of CO2 is a natural byproduct of yeast fermentation, underscoring the important role of water in Mezcal production. Now, let's look into the origins of the water used in our distillation process.

Each region's water imparts a unique character to its Mezcal, affecting the overall flavour profile. Water sources can include natural springs, rivers, or wells. At Bandida, our water flows from a mountain known as Nueve Puntas, named for its nine peaks. This mountain acts as a natural filter, enriching the water with minerals as it travels through the rocky terrain.

As the water journeys down Nueve Puntas, it collects in a dam before seeping slowly into the subsoil, ensuring a consistent water supply throughout the year. Oaxaca's infrequent rainfall poses no threat, as the mineral-rich water retained in the subsoil provides nourishment to the agave plants.

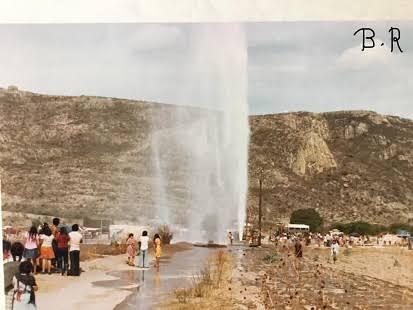

This natural filtration process creates pressurised, mineral-rich veins of water underground. To illustrate the water pressure, in 1979, a high-pressure water release propelled water up to 30 meters high. Our Mezcalero’s father passed on this picture, this is the best quality image I was able to obtain;

High water pressure in subterranean veins ensures that minerals are efficiently dissolved and carried along with the water as it travels through the mountainous terrain of Nueve Puntas. This natural high-pressure environment forces the water through dense rock formations, enriching it with a unique blend of minerals that are crucial for nurturing the agave plants. The minerals not only nourish the agave but also contribute to the complex flavour profile of our Mezcal, adding subtle notes that are impossible to replicate with water from other sources. The consistent pressure ensures a steady flow of water, which is vital in regions like Oaxaca, where rainfall is scarce.

Next I will talk a little bit about Maestro Mescalero's in Oaxaca and why they are not (yet) as well known as Tequilero's, Maestro tequileros and master distillers!